The Romantic Lie You Believe About Your Body Image

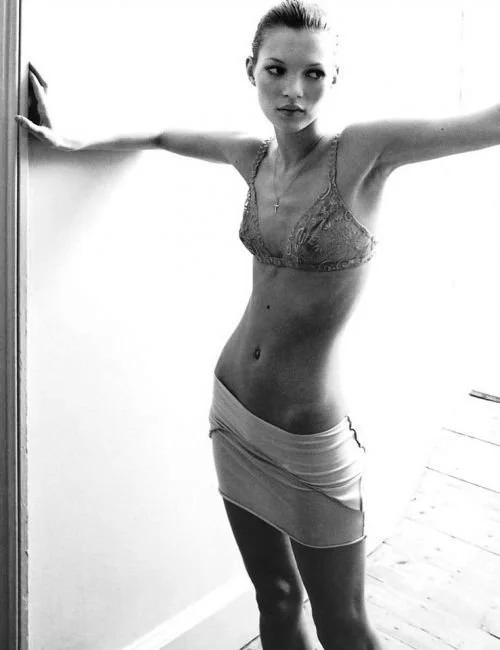

As a millennial, I endured puberty through the age of heroin chic, when the world’s top supermodels, representing the most desirable female body type, were emaciated.

Like so many other girls and women, I wanted to look sickly skinny, too. I wanted to be so thin people would whisper words of concern to me, asking if I was alright.

Over the past few decades, Western culture has seen the standards for what a desirable body type looks like shift drastically. And although the standards haven’t changed as much for men, their level of body dissatisfaction is comparable to that of women.

What also hasn’t changed over the years—for individuals of any age, race, or gender—is the level of preoccupation we have with our bodies, and the desire to achieve an appearance closer to whatever the current ideal is.

The desire to change one’s body can negatively affect one’s physical and mental health. But we can better understand what we want and why, as well as how to change our goals and experiences to support our well-being, when we view body image through the lens of imitative desire.

What do you really want?

The surface-level answer, when it comes to body goals is, “I want my body to look different.” Depending on who you are, different could mean thinner, more muscular, smoother skin, etc.

But why do you want your body to look different? What would change if your appearance changed?

Underneath, what many humans desire when they wish for a “better” body is to:

Feel more deserving of admiration

Occupy a higher social status

Feel more socially assured

Now we’re getting somewhere.

But have you ever stopped to consider why you want those things?

Why do you want what you want?

Your first answer is most likely wrong. Many people believe that when it comes to the things they want, from material goods to a certain career to a body that fulfills the current ideal, their desire arises from somewhere internal.

In Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life, author Luke Burgis refers to this misconception as “The Romantic Lie”:

The Romantic Lie is self-delusion, the story people tell about why they make certain choices: because it fits their personal preferences, or because they see its objective qualities, or because they simply saw it and therefore wanted it.

What’s really happening is, you want to look a certain way because of imitation. You don’t want what you want because of a biological drive or because you’re making a logical or rational decision.

Your desires arise because of models.

Not fashion models, but the people you choose to use as representations of what is worth desiring.

Models informing what we want happens on both an individual and a cultural level. This is how there comes to be standard, widely agreed-upon “ideal” bodies.

Your cultural socialization, which occurs through things like media messages seen in magazines, commercials, billboards, social media, and so on, mingles with your…

Physical characteristics

Personality traits, and

Interpersonal experiences (e.g. family, peers)

…to form your beliefs about your body, your satisfaction or dissatisfaction with it, and how important you believe your appearance is to your self-worth.

Many people mistakenly believe if their body doesn’t fit cultural ideals, their body is the problem. In fact, when we remove external influences, we can be satisfied with any body shape, but socialization—the models mentioned earlier—create our dissatisfaction.

This is because the more a system or idea is reinforced by those around us, the more strongly we believe in it. Appearance goals are then set based on the implicit belief that there is a way you should look, without that belief ever being consciously examined.

Taken to the extreme, this can become quite detrimental to one’s health, wherein we ceaselessly compete with each other for greater perceived status. In some cases, desire can even supercede our basic physical needs, as in anorexia nervosa.

Regardless of your current goals or health level, you can use mindful solutions that dissolve imitative desires to change the way you think about your “wants” for your body.

How do you change what you want?

Every communal unit, from families to schools, workplaces, and larger industries and institutions, has a culture that makes certain things feel more or less desirable. Consider these our systems of desire. Your goals always operate within your systems of desire. So I invite you to examine:

What are the systems of desires you operate in? What’s making you want what you want? What’s making those around you want what they want?

When you can look at these systems more objectively, you’ll have a better shot at being able to swim in a different direction.

Your values also influence your goals and desires, but not every one of your values will hold the same weight. By knowing not only what you value, but what you value most, you’ll be able to make more informed decisions about what you desire and the goals you choose to fulfill those desires.

In addition to getting to know your own wants, empathy can be cultivated to better understand the beliefs, feelings, and behaviors of others.

Empathy is one of the ways we can stop seeing one another as competitors for status, because we can share in one another’s experiences without the need to imitate them. Empathy can not only lead to a sense of shared humanity, it can perpetuate connectedness when we’re no longer viewing each other as rivals.

Similar to the way empathy can help us understand what others want without becoming identified with their beliefs, meditation can assist us in not becoming overidentified, not getting so caught up in the idea of “me” and “who I am.”

Rather than identifying with all of your beliefs and desires, allowing them to define who you are, you can ask:

What am I getting from this? Is it leading me toward or away from suffering?

And finally, when choosing what to move toward, we can use distress as a compass. Many people tend to avoid stress and other uncomfortable feelings, but what if instead of trying to avoid or diminish your distress, you used those challenging emotions to better understand yourself? You can accomplish this by asking questions like:

What does distress/discomfort/displeasure feel like? How is that different from comfortable/pleasant feelings? Where is my discomfort arising from?

Rather than compulsively or mindlessly reacting to your discomfort, you can mindfully observe and approach your uncomfortable thoughts and feelings with objective curiosity in order to help you discover what makes you feel truly happy or fulfilled.

Understanding where your appearance-related desires come from is one of the ways in which you can feel more at home in your body, which is why examining your thoughts is one of the foundational skills taught in Food Body Self®.

Whether you want to silence self-criticism, feel more confident about the way you look, or learn to love your body, changing your relationship with your body will require you to change the way you think.

When you understand how you’re being influenced, rather than accepting socially prescribed desires, you can break the mindlessness of cultural ideals to determine more authentic, deliberate goals for yourself and your body.